One January afternoon last year, a bouquet of balloons arrived at Karen Rose’s residence in Delray Beach, Florida. She wasn’t expecting a delivery, since it wasn’t her birthday or wedding anniversary, and she thought someone had made a mistake until she noticed the words “AND NOW?” printed on each balloon.

“AND NOW?” is the prompt that follows every action on ECHO, a 34-year-old text-based social network that still hosts a community of former and current New Yorkers. When you log in: AND NOW? After checking who’s online: AND NOW? Upon joining one of ECHO’s chat rooms, called conferences: AND NOW?

And now Rose, whose handle was KZ, was presented the same question, six and a half years into a battle with lung cancer that she’d documented on a section of ECHO devoted to health. When she notified the community that she was turning to hospice care, her fellow “Echoids” responded with the balloons, along with flowers and chocolate.

Then last spring, ECHO’s founder, Stacy Horn, announced KZ’s death on ECHO. KZ was one of the platform’s 20 inaugural members, having joined in its first year at Horn’s invitation and remained until her death at 72. She was the host of the network’s sex conference, a real estate agent, artist, self-proclaimed “dance snob,” taiko drummer, tennis player, and general “doer.” People of such eclectic interests were central to establishing the vibrant cultural personality of this online community.

ECHO stands for “East Coast Hang Out,” and when Horn founded it, she wanted to create a digital space that was social and unequivocally New York. Members had to meet two requirements: they had to be geeky enough to navigate a cumbersome, text-based digital platform in the early days of the internet, but culturally in tune enough to foster the types of conversations you might hear at a West Village dinner party. Horn enlisted her graduate school friends (she was a recent graduate of New York University’s interactive telecommunications program), as well as members of other bulletin-board-style platforms. One primary source of inspiration was the California-based online community known as the WELL (for “Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link”), started by Stewart Brand in 1985. Brand is well known for being a counterculture impresario in the Bay Area during the 1960s, editing the widely distributed Whole Earth Catalog. Just as the WELL brought together experimental, self-sufficient individuals who foresaw the endless possibilities of computers, ECHO defined the New York web scene and influenced the design of contemporary social networks, creating lifelong friendships in the process.

When ECHO was founded, the World Wide Web was still being invented, and browsers weren’t a thing. Users congregated in interest-based forums, but Horn found most of them to be male-centric, heavy in technical jargon, and, just like the WELL, centered on the West Coast. She craved a destination like the vibrant and artistic 20th-century salons of Gertrude Stein’s era, where users could exchange ideas and meet one another while getting lost in discussion.

What she ended up making was a hotbed of culturally minded early internet enthusiasts—a social network before there was a term for that. Through the evolution of this ecosystem, users would meet one another and contribute to the changing digital economy by starting businesses and cultural programming. They would forever transform their lives in a way that wouldn’t otherwise have been possible, all while making a lasting mark on New York’s budding tech community. ECHO was a blueprint for the larger-scale social networks that we see today, and it serves as a reminder that behind all networks are people, with a lot of words to exchange.

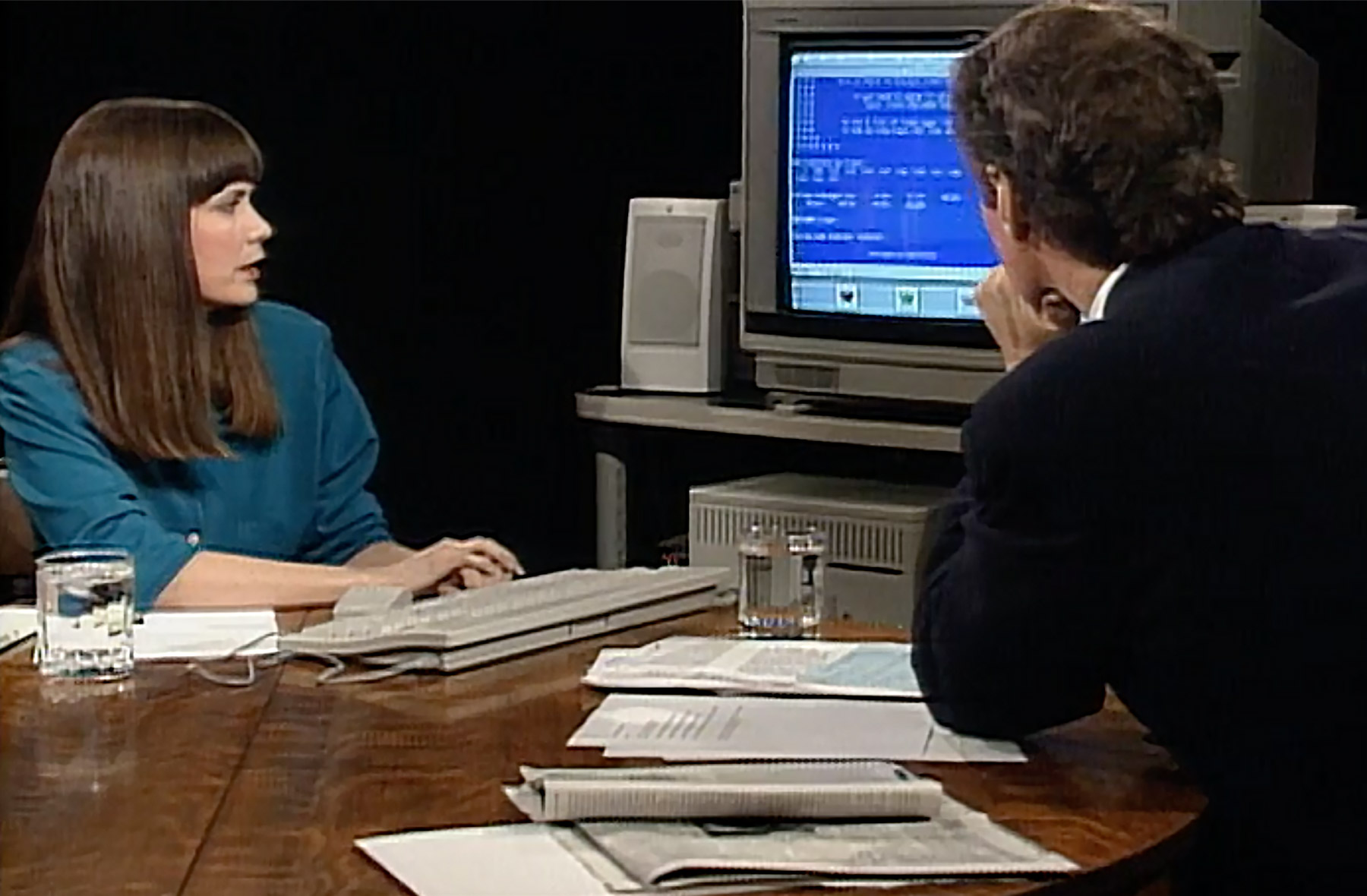

Horn, who is now 66, still lives in the same West Village apartment that was her home when she launched ECHO. When I met with her to discuss its origins, she had a neatly trimmed bob with bangs and wore denim jeans with a fitted black T-shirt—conjuring both Steve Jobs and downtown “it girl.” She said the idea for ECHO came out of her day job as a telecommunications analyst at Mobil, where she was the only woman in her department.

Week after week, she’d pitch the idea of “computer conferencing,” an efficient strategy to manage machines in different time zones that would post updates to one continuously synced document. “I would stake my entire future that this is going to be the thing,” Horn enthusiastically told the team of corporate men about her plan. She got the impression they thought the idea was laughable, and the answer was a firm no. Her boss suggested that obtaining a graduate degree would help Horn climb the corporate ladder, and while her interests were shifting toward writing, she thought graduate school sounded exciting. She picked the NYU program because it had “telecommunications” in the title, so Mobil would cover it as a work-related expense.

Horn described cyberspace as the most erotic medium because of the anticipation and thrill that messaging provided.

Horn expected the program to be as dry and technical as her job designing telecommunications networks, but she was taken by the school’s experimental philosophy. She wrote a play called Corpse in Space that took the form of a conversation between a talking sofa, a praying mantis, and a dead saint. As she went to turn it in, a pang of doubt overcame her; she sheepishly placed her draft at the bottom of the stack of assignments and quickly left the room. The next time she was at school, Red Burns, ITP’s renowned chair, brusquely called out, “Stacy Horn! Stacy Horn!” Horn interpreted the tone as ominous, but to her surprise, Burns embraced her and said her paper was more fun than anything she’d read in years. In that moment, Horn’s worldview changed. “Oh my god, I can just go crazy and somebody might actually like it,” she recalls thinking. Technology didn’t have to be cold and impersonal. She became dedicated to experimentation and play in her work.

Back at Mobil, Horn decided that if her team could see a social network in action, they’d never go back. She started a trial program called MoNet (a portmanteau of “mobile network”), but to her dismay, it flopped. (A few years after she left Mobil, she says, a former colleague told her that everyone on the team had agreed to tank the project. They were concerned that the platform would expose everyone’s work habits and amplify their mistakes.)

Upon leaving Mobil, Horn used the software behind MoNet, known as Caucus, to set up ECHO. She pitched it as a social community where interesting, thoughtful New Yorkers could connect about the books they were reading and the places they were going, and ultimately get to know one another on a deeper level. She wanted to create a “small town” feeling where residents had a sense of pride.

None of the investors she approached were interested. At the time, she says, the consensus was that the only people who would want to talk to others online were socially inept weirdos. So she started the platform with $20,000 of her savings and ran it out of her apartment.

In those days, most people had only one phone line at home, while businesses would have a few more. Horn asked NYNEX, the local phone company, to connect additional lines to her apartment. Before long she needed up to 24 lines, which was more than the maximum available for the whole building. But with the internet beginning to take off, the phone company realized that soon she wouldn’t be the only one needing additional capacity. NYNEX ripped up the street and installed new cables that would support not only ECHO but the neighboring buildings’ communication needs for the foreseeable future.

Horn recalls her neighbors being irritated with the logistics of an internet business running out of the apartment complex, particularly during the cable installation, but in the end, their neighborhood was one of the first with stronger internet connections that everyone could enjoy. Back in her apartment, ECHO’s modem, housed in a custom cabinet with crimson sequins along the edges and gold tassels in the front, would get so hot it warmed up the whole space. ECHO’s server bounced around New York before ultimately moving to a more stable facility in Oregon.

At its peak in the late ’90s, ECHO had 3,500 members. Among them: writers, artists, musicians, actors, therapists, and even, briefly, John F. Kennedy Jr. Horn hand-picked early members to help seed the community. To make women feel welcome, she gave them free one-year memberships (ECHO cost $10 a month and $4 an hour for online time when it first launched) and made sure to assign women to host various conferences. Those efforts paid off—40% of ECHO’s users were female at a time when women made up a tenth of the online world. Membership snowballed after the appearance of a 1990 New York Times story headlined “Coming to the East Coast: An Electronic Salon,” placing ECHO at the forefront of New York’s “Silicon Alley.”

To extend the artistic component of the platform, Horn did outreach at art openings and museums. She and David Ross, then director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, created an ongoing series in which they’d pick a topic related to visual culture and invite a panel of experts to discuss it at a nonprofit performance space in the East Village. Other events the community organized included “Dinner Theatre of the Mind,” a monthly seminar of philosophical discourse held by two members known as “Neandergal” and “Miss Outer Boro 1991”; an independent film group; and the World Wide Web Artist Consortium, where participants met in real life to talk about the internet.

“There wasn’t a velvet rope to get in, but you had to have certain chops to be able to hang with those people.”

Kyle Shannon, an actor and graphic designer who founded the consortium, says he initially joined ECHO to surround himself with people who knew more about the web than he did. “There wasn’t a velvet rope to get in, but you had to have certain chops to be able to hang with those people,” he says.

When Shannon and his wife, Gabrielle, tried to post an e-zine called Urban Desires online, his images didn’t load, and he logged on to ECHO to see if anyone could help. A fellow Echoid, Chan Suh, responded and revised his code. A month after the e-zine launched, in 1994, Shannon learned that the French newspaper Libération had run a full-page article about it. “The distance between putting something in the world and having an impact just went to zero,” he said after seeing the publication on a newsstand in Times Square. By 1995, Urban Desires had 100,000 site visits a day. He later partnered with Suh to found an online marketing business called Agency.com. The company was bringing in $200 million in revenue at its largest before Omnicon acquired it in 2002, Shannon says, and made interactive websites for Fortune 500 companies, including British Airways’ first ticketing system and Sirius Satellite Radio’s online player.

There were weekly “F2F” (or face-to-face) sessions at downtown watering holes. After the parties ended, members would log back on and keep chatting, sometimes in private conferences. Online romances blossomed. In her 1998 book Cyberville: Clicks, Culture, and the Creation of an Online Town, Horn described cyberspace as the most erotic medium because of the anticipation and thrill that messaging provided. “Stacy always likes to say that [there are] children [who] wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for ECHO,” says Jim Baumbach, who met his wife, Liz Margoshes (a.k.a. Neandergal), on the platform in the early ’90s. Now they’re married, 70-something therapists who still use ECHO daily— even going as far to send “YO’s,” ECHO’s version of a direct message, to one another while in the same East Village apartment.

Shannon attributes ECHO’s success to its rootedness in a specific local scene. “A strong culture, by definition, has exclusion criteria, whether they’re explicitly stated or not,” he says.

Omar Wasow, an assistant professor at UC Berkeley, was on ECHO in his college years, when he was a student at Stanford. He’d grown up in New York, so the regional aspect of the platform intrigued him, as did the focus on discussion. But Wasow says he was more of a lurker than a participant. After college, where he studied race and politics and taught entrepreneurship at a nonprofit helping former drug dealers start businesses, he moved back to New York. Living in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Fort Greene, which was going through a Black renaissance, he became part of a large community of Black professionals. He realized he wanted to create a digital space that was inspired by ECHO but reflected his own interests and experience of the city, for a community he connected with beyond the screen.

In 1994 he started New York Online, a social network focused on highlighting a multicultural experience in New York City. In a New York Times article from the year of its launch, he compared the platform to the subway: “It’s a network that connects you to the whole city, and you are always surrounded by a really eclectic mix of folks.”

A few years later, as the internet became more widespread, he launched BlackPlanet, a platform focused on Black Americans that became a precursor to social media platforms that updated in real time, like Myspace and Facebook. When Wasow sold the site, in 2008, it had around 20 million members and was the fourth-most-visited US social network. Kanye West mentioned flirting with women on BlackPlanet in his 2004 song “Get Em High.” Wasow says that both ECHO and his platforms challenged the dominant ideas about who these technologies were for, why they should be used, and who should use them: these communities “were prototyping the future in which the internet belonged to everyone.”

Both Wasow and Horn have experienced the pains of legislating a social network. On BlackPlanet, there was a “fuck filter” that searched for curse words in screen names and blocked them. But when a user with the last name Bowcock was prevented from accessing the site, the need for a human touch became clear. ECHO’s population was always small enough to afford a more casual style of rule enforcement. Most incidents could be resolved with a face-to-face meeting, says Horn, who is still involved in everyday administration of the social network—“babysitting us senior citizens,” as one user recently put it.

Today, with just 43 active users, ECHO is a much quieter destination than it was in the ’90s, but members still chat and bicker with one another. After one recent dispute between three members, two of them were demoted to “read only” and Horn considered closing the platform. When she announced what she was thinking, users balked: “If a plea would help you change your mind, ECHO has seen me through some of the most dramatic times of my life, and that is entirely due to your vision and your patience. I hope you will find a solution,’’ a user named Schuyler Sue wrote.

When not online, Horn spends her time working at the ASPCA and writing; her seventh book is in progress. Although she is not yet ready to step away from ECHO, she has considered passing it on to someone else to administer. And when it ultimately fades away, she plans to donate ECHO’s archives to the New-York Historical Society, securing any private conferences from release until those who participated in them are no longer living. She takes pride in the online culture she helped foster, one in which language documents a communal experience of passing time.

“On ECHO you own your own words,” Horn says. It’s one of a handful of guidelines that help keep the peace.

Nika Simovich Fisher is a writer, graphic designer, and assistant professor of communication design at Parsons School of Design in New York City.

Comments

Post a Comment